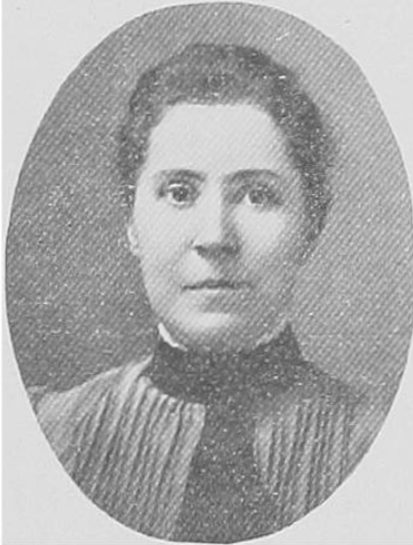

Belles’ Attempt to Vote

In April 1888, Belles went to the polls in Flint to vote for school trustees under a law passed by the state Legislature. This new law used the word “person” to define qualified voters. The state constitution, on the other hand, specifically said “men.” It made no provisions for women voters.

In fact, many people thought women were unable to make political decisions. They believed women should depend on their husbands to vote in their best interest. Suffragists like Belles thought otherwise.

At the polls, Belles offered to swear to her qualifications. She was over 21, married, owned taxable property, and had lived in Flint’s Third Ward with her seven-and-a-half year old daughter Jennie for three years. However, the election inspectors, William A. Burr and two others, refused to receive her ballot.

The inspectors may have known the law would be tested that day. According to one account, “a number of ladies” were turned away, but this detail does not appear in court records. The elections inspectors also sought legal advice before refusing Belles’ ballot.

To settle the question, Belles sued in Genesee Circuit Court and won. The election inspectors appealed, and the Michigan Supreme Court upheld the lower court. Women could qualify to vote in future school elections. Despite its significance, the decision received little public attention.

A New Direction for Belles

Belles – a Vermonter and former resident of Oakland County, had friends and support in Flint. She raised money for her case with help from a local temperance (anti-alcohol) group, and organized a women’s suffrage club that met in her home. However, life led her out of state – possibly before her next vote.

While awaiting the high court’s decision, Belles filed for divorce. Critics of women’s suffrage often warned marital breakups would result from expanded voting rights, and Belles’ activism may have proved a tipping point in what was likely a rocky marriage. She gained custody of daughter Jennie and headed to Cleveland. Her husband remarried within a year and stayed in Flint.

New Life in Ohio

With no obvious family connections in Ohio, Belles’ reformist friends may have encouraged her to resettle there. Cleveland offered several temperance organizations, and she immediately took an active role.

In Flint, Belles ran a private school from the family home, so she turned to teaching in Cleveland schools. Eventually, she taught drawing at East High School, a grand “20th-century schoolhouse” that opened in 1900.

Talented and resourceful, Belles undoubtedly faced challenges. She never remarried, so she depended on her own income, that of her daughter, and eventually her daughter’s husband to make ends meet. She moved numerous times over the years, and she died in 1916, possibly while living at Dorcas Home, a charitable institution for ill and destitute women. Eva Belles was just 59 years old.

Belles’ Legacy

Although Eva Belles’ attempt to vote received little public notice and the fight for full suffrage took three more decades, her case became an important precedent. For the first time, the Michigan Supreme Court recognized women could qualify to vote under state law. Belles v Burr became widely known through its publication in legal digests, and it was cited in later court cases. Following its centennial, the State Bar of Michigan designated the case a Michigan Legal Milestone.